You can run but you can’t hide! Why the fear of old age is making aliens of the frailest

Author: Debs Peyton

One of Faith in Later Life’s Ambassadors, Silver Cord‘s Debs Peyton shares some of her findings from studies and research she undertook for her recent dissertation…

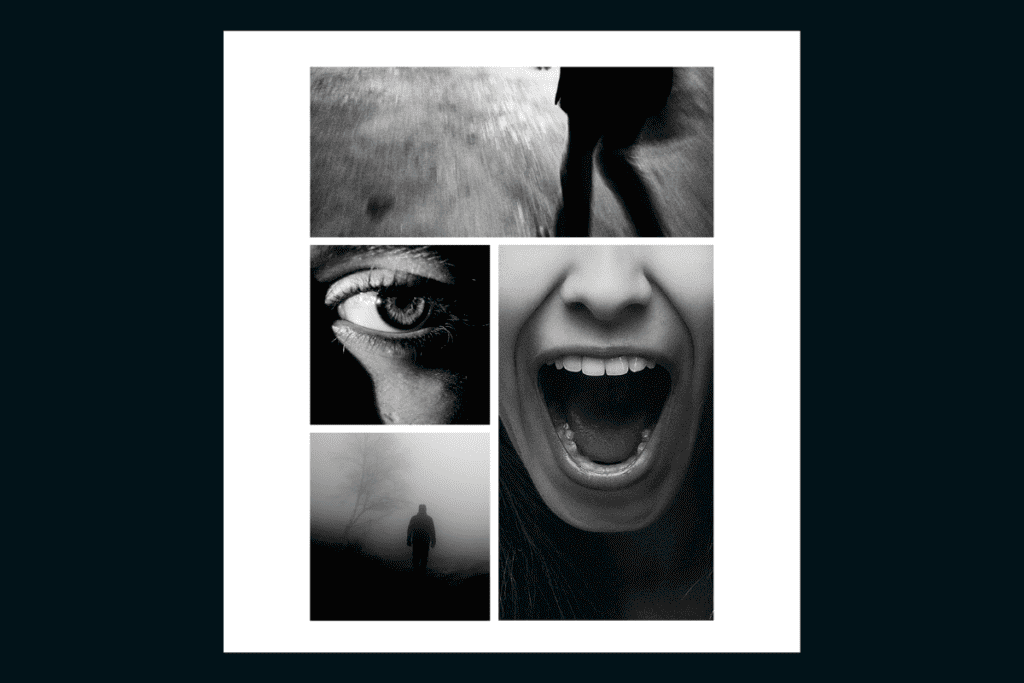

To avoid too much confusion (and offence!), let me promptly clarify the term ‘alien’. I’m referring to the Hebrew word gār, scattered throughout the Old Testament, meaning ‘stranger’, ‘sojourner’ and yes, ‘alien’. Someone who seemingly is from another land and to be welcomed and respected under God’s instruction (e.g. Ex.23:12; Jer. 22:3). Not quite the terrifying and provocative picture above. Hang on though, there is a reason I chose the picture…

Recently I completed my dissertation in Third Age Mission & Ministry at Cliff College (I often need to clarify it is not a Star Trek course). Exploring the concept of high-level care dependency (fourth age), I received feedback from 70 people who regularly attend an Evangelical church, aged 65-75 and currently experience relatively good health. I wanted to explore current perceptions of dependency and what difference the Christian faith makes considering loss of independence, sense of purpose, feeling a burden and the prospect of being dependent on state care. (Age UK report there will be a 67% increase in disabled older adults in the next 20 years).

The research showed a consistent level of serious to grave concerns around the themes of dependency in over half of the respondents. Unsurprisingly, the notion of being dependent on state care was disproportionately high with 84% expressing serious concerns. Although the Christian faith featured highly for over half of respondents, contributing to a meaningful outlook when considering dependency, 40% still saw it as having little or no impact on their perceptions.

The propensity to view ‘being’ as inferior to ‘doing’ was a consistent theme throughout the research. Gerontologist, Thomas (2004), along with a plethora of writers in this field, describes the human life-cycle as this: We start, as children, in a state of BEING (dependent on others), through the adolescent transition into adulthood, the emphasis becomes our DOING (working, caring, parenting). Finally, we go through a stage of ‘senescence’ into elderhood, where our dominant state becomes BEING. Thomas adds: ‘Far from its crude caricature as a second childhood… elderhood offers a richness that can only be known near the end of a long life… a life defined by the experience of BEING-doing. This is a gift of great value’ (p.127).

Thomas suggests that since the mid-twentieth century, along with advances in business and technology, adulthood’s ego became over-inflamed, seeking power and prestige alongside the usurping of traditions. ‘Postmodernism’ in the West also led to changes in identity formation through social structures (e.g., the church or family) in favour of individualism, subsequently perpetuating a more individualistic view of ageing. The implication is that elderhood or transitioning through ‘senescence’ has nothing to offer but loss of identity, loss of societal value and ultimately, loss of hope.

Over 12 years of ministry, I have encountered many times this sense of meaningless existence when physical functioning has weakened. One 90-year-old expressed sentiments capturing this mindset: ‘there’s nothing left for me now – all I’m good for is ‘knacker’s yard!’. These self deprecating reflections were painful to hear. The teams I worked with saw honour and value, the great privilege of being allowed into the last chapters of someone’s story, rich treasures of life experience and the inherent worth of every human life, created in the image of a relational, Trinitarian God.

We cannot explore how we change the deeply embedded, anti-elder narrative until we recognise the cultural norm that dominates media, literature, and the subconscious. Mayer (2011) refutes old notions of lifecycles, coining the term ‘amortality’, described as the revolutionary perspective of agelessness: ‘liv[ing] in the same way, at the same pitch… from late teens right up until death’. The largely subconscious but apparent side-effect of a ‘forever young’ mentality is a new form of ageism that celebrates older people to the extent that they are perceived to be or act younger. Think about it. Why is it such a compliment when someone says you don’t look your age?

There is, of course, something to be applauded about a radical approach to ageing and encouraging continued contribution and cultural citizenship of older people, especially considering the systemic ageism pervading society and churches. However, if the concept of ‘ageing successfully’ is tantamount to reflecting the best of adulthood in terms of strength, youthful looks and autonomy, there is a flip side to that coin that has the most devastating consequences for those in the ‘failing’ fourth age.

Nouwen & Gaffney were calling this out back in 1974. In their book ‘Ageing’, they highlight BEING in old age will always be devalued while DOING is considered superior. Mayer even acknowledges this disassociation with the fourth age as necessary for ageless living: ‘the amortal lust for life.. make[s] us peculiarly unsuited to cope with frailty and death’, ‘people reject or blot out the notion that we will be forced to rely on others’. It is this denial of aging, not aging itself that is perpetuating the ‘cult of adulthood’ as Thomas puts it, and subsequently alienating elderhood. So how, as Christians, do we respond to this? We cannot avoid it, whether considering our own ageing or being part of an ageing society and church. Four initial responses to consider:

1. Offer presence. Jesus always moved towards those whom society perceived as outcasts. There are many opportunities to galvanise the local church by offering presence to those affected by dependent living. Local churches are well-placed to be one of the key providers of stimulus in care homes. There is potential for chaplaincy, befriending services, transport to church activities and intergenerational connections. We have experienced all-age connections to be a healing tonic to those affected by family breakdown and families dispersed. Although our presence demands compassion, this is not with the view of victimising or patronising those in the fourth age, but with the hopes of retrieving the truth that we have yet much to learn by being in the presence of our elders.

2. Face your fears. ‘No guest will ever feel welcome when his host is not at home in his own house’, wrote Nouwen & Gaffney. Christian and secular gerontologists agree we must first befriend our own ageing. Whilst we stay in a position of denial, we remain emotionally disconnected from truly being able to express compassion and risk offering, at best, a level of ‘dangerous pity’ as Augustine described it, not truly connecting with the pain of the other (Vosman & Baart, 2008). By acknowledging the primordial commonality of growing older and being authentically present, there arises the opportunity for true connection. Nouwen & Gaffney write: ‘Compassion does not take away the pains and the agonies of growing old but offers the place where weaknesses can be transformed into strengths’.

3. Be real. The transition to ‘elderhood’ is not one of ease, even with faith in Christ. There is surely something very human about grieving a life we have known if our circumstances require care dependence on others. Biblical hope is not fanciful denial, nor triumphalism that whimpers ‘praise God’ when inside you are screaming. As Christians, we live our lives under a different narrative, under the Great Story, Easter-shaped, with the interplay of suffering and glory, weakness becoming a strength and dependency as the base line to salvation. Religion starts with a ‘feeling of absolute dependence’, wrote de Lange (2015) – any remote leaning to self-sufficiency and autonomy is the antithesis of the gospel.

4. Have a theology of suffering. The paradox of suffering and glory permeating the Christian life is exemplified through the crucifixion and resurrection. The cross did not look successful – for Jesus’ followers, it appeared to be an utter failure, weakness, shameful even. But hanging on the cross, in a helpless and immobile state, God was achieving the most glorious act in the whole of human history. If the ‘chief end of man’ in response to God’s loving kindness is to ‘glorify God and enjoy him forever’, then although our service to Christ is an act of worship, our enjoyment of him is also not defined by our practical/physical contribution. I read a quote from Sam Allberry recently: ‘We still find ourselves thinking the power of Christ must be in the biggest church, the best church, the brightest pastor. But the power of Christ is seen in weak men and women who are clinging on to the Lord’. There is something profound to learn in the presence of believers in the fourth age as they learn to trust in the grace of God for each day, wholly aware of their own limitations (Nouwen & Gaffney, 1974).

In my research questionnaire, someone commented: ‘I am hoping to cross that bridge when I come to it, but not before’. I would argue, it is conducive to healthy spirituality to face the very issues that threaten our sense of autonomy and identity. Part of being a thoughtful follower of Christ is to periodically ask the question: ‘who am I, without all that I do?’.

The systemic ageism, the ‘cult of adulthood’, living agelessly and for the large part, the loud silence in the UK church on these issues only suggest the themes are worthy of further theological exploration and airtime within local church settings. Without this, the fourth age will suffer continued injustices as ‘aliens’ and secondary citizens and we will subsequently miss the beauty to be discovered only through welcoming the stranger and facing the commonality of human weakness that so permeates the Christian faith and offers hope in the face of despair.

Bibliography & Further Reading:

de Lange, F. (2015). Loving Later Life: An Ethics of Aging. Cambridge: Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Mayer, C. (2011). Amortlity: The Pleasures and Perils of Living Agelessly. London: Vermilion.

Nouwen, H. J., & Gaffney, W. J. (1974). Aging. New York: Doubleday.

Thomas, W. H. (2004). What Are Old People For? How Elders Will Save the World. Acton: VanderWyk & Burnham.

Vosman, F; Baart, A. 'Being Witness to the Lives of the Very Old', Sociale Interventie. 17(3), pp.21-32.